Collaboration, imagination and designing the future substance of STEM: insights from a cross-institutional, virtual workshop convening

By: Benjamin Scragg

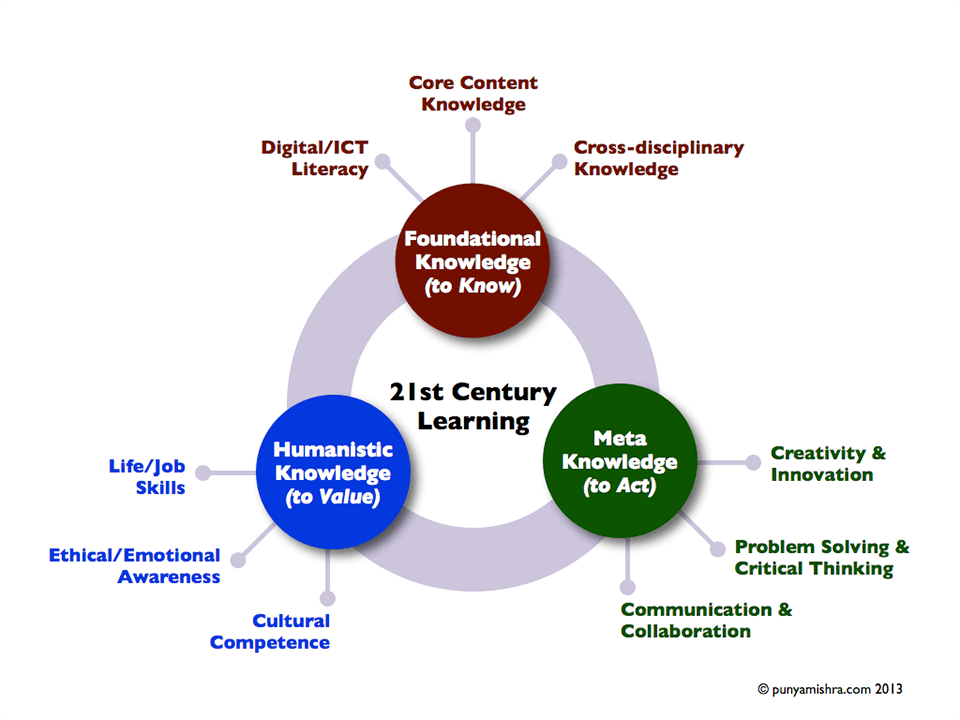

Design“What knowledge is of most worth?”

It’s a question that the English philosopher, Herbert Spencer, asked over a 100 years ago in an essay with the same name. It’s also the foundational question we asked as part of the Future Substance of STEM Education project, in which we sought to respond to a call from the National Science Foundation to envision and respond to the looming challenges to the curriculum of undergraduate STEM programs. In a rapidly changing and complex world, with an increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) future, Spencer’s query challenged us to explore what future STEM students will need to know and be able to do in order to help their fellow human beings, communities, and planet flourish in the time of the Anthropocene.

In order to imagine and instantiate responses to this fundamental question, our office – in collaboration with ASU’s Center for Education Through eXploration (ETX), and supported by Carleton College’s Science Education Resource Center (SERC) – hosted the Future Substance of STEM Education in in October 2020. The week-long, virtual workshop studio included more than 100 educators, researchers, and STEM practitioners working across 25 teams to collaboratively develop new programs and curriculum materials. Our fearless leader, Punya Mishra (Associate Dean of Scholarship and Innovation, MLFTC), and Ariel Anbar (President’s Professor, School of Earth and Space Exploration and School of Molecular Sciences; Affiliate Faculty, MLFTC) were the project’s co-PIs. To learn more about the workshop and its outcomes, please check out the project website here.

While the workshop took place in October 2020, we began planning in the spring of 2019, and worked for almost 18 months to bring the workshop to fruition. Through rounds of discussion and design and even through a global pandemic, the organizing committee worked regularly to hone the vision and scope of the project, draft proposals, recruit organizers and participants, and to iterate and reiterate the program and its desired outcomes. Originally scheduled as an in-person workshop to be held at ASU’s Barrett & O’Connor Washington Center, the project moved to an online format, using Zoom and SERC’s Serckit platform as collaborative workspaces for the teams to draft and revise their product proposals. The workshop was preceded by a series of webinars designed as a kind of provocation for participants, and included expert insights and questions from a number of notable guests.

Lessons learned, or: what is of most worth when working virtually across institutions?

Taking a cue from Spencer, I think it’s worth spending some time reflecting on the experience of planning and executing this workshop with colleagues across the country before and during the disruption of COVID-19. Here are some important takeaways I have learned as I reflect on this project:

- Use the medium to your advantage. Clearly, the largest constraint to planning and executing the workshop was the diaspora of both the organizing committee and the participants. We set out initially to plan a workshop experience based on the principles and practices of a design studio, marked by design and design thinking protocols and exercises, team work-time to iterate, ample space to visualize and prototype, and scheduled group presentations with shared critiques. Once we knew we wouldn’t be able to host an in-person convening, our focus shifted to exploring the virtual methods and mediums that would best support a synchronous-yet-remote workshop delivery where teams could still be creative and productive without the energy and buzz that often comes from collaborative, in situ gatherings. Through collaboration with SERC, we realized the wiki-style editing capabilities of the Serckit platform could help the teams create living, iterative drafts of their products. Through Zoom video conferencing, while now ubiquitous and occasionally obnoxious to many, we could create unique virtual team workspaces and shared community spaces for whole workshop gatherings and small group critiques and feedback sessions. All told, through this format, along with our collaborative and shared infrastructure at the organizing committee level, we were able to clearly and effectively orchestrate a dynamic workshop to a dispersed, busy, and diverse group of participants and stakeholders.

- Leverage the strengths of your team. An endeavor this big and complex was never going to be the work of any one person or office. The organizing committee included invaluable contributions from Cathy Manduca at Carleton College and the SERC team of Sean Fox and Monica Bruckner; Trina Davis at Texas A&M-Commerce; Larry Ragan at Ragan Education; and the ETX staff including Ariel Anbar, Joe Tamer, Chelsea Davis, and Chris Mead. From OofSI, Punya and I contributed to the organizing committee, along with Elizabeth Mirabal’s administrative support. I often tell friends and colleagues that collaboration at ASU seems to happen at a scale and pace that I’ve never quite experienced in any other workplace. Of course there are smart, competent people everywhere, but the experience of planning this project cemented for me the power of what teams of diverse expertise, backgrounds, and interests can yield. The ETX team from ASU and Trina Davis from Texas A&M-Commerce brought an incredible network of people to the table, including most of our organizing committee, as well as for participant recruitment. Cathy and the SERC team brought integral knowledge of delivering programming on NSF projects, as well as the technology infrastructure know-how to deliver the workshops. For our parts, I think Larry Ragan, Punya and I brought an interest in the participant experience and an engaging delivery. All told, I think our collective strengths enabled the project to go further than any of us could have as a smaller unit.

- Center the humans, surround with the science. Being human-centered is one of our most important design principles and mindsets, and I believe the power of working toward this principle enabled the workshop to be successful at a fundamental level. To start, the very framework of the workshop itself relied upon a domain of humanistic knowledge that made the case for knowledge that goes beyond mere content, facts and theories. At the level of the workshop organization, our team recognized early on that we were not nearly diverse enough in backgrounds, both in terms of demographic makeup and professional experiences. As a result, we sought to become more inclusive with respect to representation, and that carried through to our selection of workshop participants. Our pre-workshop webinars emphasized the need for equity and justice in STEM education, and our workshop programming and product design encouraged participants to account for representation, equity and access in their final products.Finally, our OofSI team prides itself on engaging and empathetic delivery. There is always a large responsibility and power that we assume when we facilitate, host or deliver learning experiences to others, so we are attentive to being good stewards of others’ time and energy. I was proud to share the screen and hosting responsibilities across the organizing team, and am grateful to Larry Ragan for being warm, compassionate and affable. I am also grateful for the participants who sought to create an inclusive and respectful environment during the webinars and workshop sessions, and for their open acknowledgement and addressing of concerns or corrections to promote inclusivity throughout the sessions.

While the workshops have concluded, the lessons learned from this experience will certainly carry our team into future endeavors, and they leave me excited for future collaborations. The work of the Future Substance of STEM Education itself continues as well, as we have ongoing plans to build upon and sustain the community we’ve established this year. While the future remains uncertain and complex, the necessary and human-centered work of this project holds a promising response for Herbert Spencer.

Framework for organizing deliberation on the future substance of STEM education. Graphic from Kereluik, Mishra, Fahnoe, & Terry (2013)

Kereluik, K., Mishra, P., Fahnoe, C., & Terry, L. (2013). What knowledge is of most worth: Teacher knowledge for 21st century learning. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 29(4), 127-140.